Lincoln's "Whites Only" Plan for America and the North's Horrific Treatment of Blacks

Summary and Comments on Chapter 2 of Thomas DiLorenzo's "The Real Lincoln"

Impeaching Lincoln’s Moral Character

Thomas DiLorenzo begins Chapter 2 of his book by attacking Abraham Lincoln’s moral character. Although officially treated as divine with a Zeus-like statue in Washington, D.C., Lincoln is reduced to a “master politician” by DiLorenzo, a term with all sorts of negative connotations.1 Although conceding that Lincoln was a successful politician, DiLorenzo criticizes him for “saying one thing to one audience and the opposite to another. Lincoln’s speeches and writings offer support for both sides of many issues.”2 DiLorenzo’s explanation for Lincoln’s behavior is quite simple. “It was a textbook example of a masterful, rhetorically gifted, fence-straddling politician wanting to have it both ways,” DiLorenzo writes, “in favor of and opposed to racial equality at the same time—in an attempt to maximize his political support.”3 DiLorenzo states his case this way:

While adamantly opposing “social and political equality” of the races, Lincoln took the contradictory position of also defending—at least rhetorically—the natural rights of all races to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, as enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, and referred to slavery as a “monstrous injustice.”4

These contradictions are fairly easy to illustration. For example, on the one hand, “Lincoln is often hailed as a champion of the dictum in the Declaration of Independence that ‘all men are created equal,’”5 but on the other hand, Lincoln expressed white supremacist views when he said that he was “in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position.”6

I do have one concern about DiLorenzo’s discussion in this section of his book. He cites Austrian school economist Murray Rothbard who bluntly says that “Lincoln was a master politician, which means that he was a consummate conniver, manipulator, and liar.”7 Without providing any evidence to support the allegation that Lincoln was a “conniver, manipulator, and liar,” DiLorenzo abruptly starts the next paragraph and quickly moves onto another topic. My fear is that DiLorenzo is engaged in an ad hominem attack on Lincoln. DiLorenzo, I think, should have cited Rothbard’s original piece in order to show that Rothbard is attempting to make a substantive argument:

Lying to South Carolina, Abraham Lincoln managed to do what Franklin D. Roosevelt and Henry Stimson did at Pearl Harbor 80 years later—maneuvered the Southerners into firing the first shot. In this way, by manipulating the South into firing first against a federal fort, Lincoln made the South appear to be “aggressors” in the eyes of the numerous waverers and moderates in the North.8

With this additional information, I can now go to other sources to see if what Rothbard says is true or not.

Making America “Whites-Only” Using “Colonization” (i.e., the Deportation of Blacks)

Lincoln got his bad ideas from Henry Clay, according to DiLorenzo. In the previous chapter, Lincoln adopted Henry Clay’s “American System,” which was an attempt to impose British mercantilism on America. DiLorenzo, of course, rejects mercantilism because he supports free market economics. In this chapter, Lincoln inherited from Henry Clay the colonization idea.9 Colonization means “eliminating every last black person from American soil.”10 Lincoln, for some reason or perhaps for some reasons not explained by DiLorenzo, kept changing his mind about the deportation destination or destinations. Various possible locations are mentioned by DiLorenzo including:

Liberia

Haiti

Africa

Central America

Danish West Indies

Dutch Guiana

British Guiana

British Honduras

Guadeloupe

Ecuador

“Linconia” (a proposed Central American colony)11

One reason why Lincoln wanted “the peaceful ‘deportation’ of blacks” was because he wanted to give all the land to “free white laborers.”12 Lincoln’s concerns for “free white laborers” also influenced his views on the issue of extending slavery into the new territories, the topic that will be covered next.

Lincoln Opposed the Extension of Slavery into the New Territories to Protect White Free Labor

According to DiLorenzo, “none of the four political parties that fielded presidential candidates in the 1860 election advocated the abolition of Southern slavery” because “doing so would have meant political suicide.”13 Republican politicians at this time in history were primarily concerned about “the extension of slavery into the new territories” because they feared that “slaves would compete with white labor in the territories, which the Republican Party wanted to keep as the exclusive preserve of whites.”14 DiLorenzo quotes Lincoln’s Peoria, Illinois, speech of October 16, 1854 in which Lincoln explained why the Republican Party wanted to stop the extension of slavery into the new territories:

The whole nation is interested that the best use shall be made of these territories. We want them for the homes of free white people. This they cannot be, to any considerable extent, if slavery shall be planted with them. Slave states are the places for poor white people to move from. . . . New free states are the places for poor people to go and better their condition.15

One thing that bothers me about this is that it seems to imply that white free labor cannot compete with black slave labor. It sounds like if there were a direct competition between black slave labor and white free labor in the new territories then black slave labor would win and the white losers would be forced to move somewhere else to earn a living. The only thing stopping this is for big government to step in and use its coercive powers to keep black slavery out of the new territories. This implies that big government is actually a good thing (because defeating slavery is a good thing). But such a conclusion contradicts DiLorenzo’s main thesis which is that America should support limited Jeffersonian government and not centralized Hamiltonian big government. My point here is that I think DiLorenzo needs to do more at this point to defend his main thesis. Was Lincoln wrong to worry about the extension of black slavery into the new territories? Was white free labor capable of defeating black slave labor without government intervention?

Perhaps I can come up with DiLorenzo’s defense for him. DiLorenzo normally and repeatedly denigrates the system of black slave labor because he sees it as a system artificially propped up by the government. Basically, the slaveowners were being subsidized by the Federal government because of the Fugitive Slave Act which

socialized the enforcement costs of slavery, thereby artificially increasing the price of slaves. That is, Northerners were compelled by law to round up and return runaway slaves, solely for the benefit of Southern slave-owners. Abolition of the act would have caused the price of slaves to plummet by dramatically increasing the costs to slave-owners of enforcing the system, thereby quickening the institution’s demise.16

Unfortunately, Lincoln was a strong defender of the Fugitive Slave Act. According to DiLorenzo, Lincoln

strongly defended the right of slaveowners to own their “property,” saying that “when they remind us of their constitutional rights [to own slaves], I acknowledge them, not grudgingly but fully and fairly; and I would give them any legislation for the reclaiming of their fugitives. That is, he promised to support the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which obligated the federal government to use its resources to return runaway slaves to their owners.17

So perhaps Abraham Lincoln was stuck in some sort of “death spiral” of government interventionism. First, he supported the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a government intervention that artificially propped up black slave labor. But this first intervention created a problem for him. Black slave labor became an ominous threat to white free labor. Since the Republican Party was “the white man’s party,”18 Lincoln had to do something to protect his voting base. So, to fix the problem that the first intervention had created, Lincoln resorted to further government interventions, such as deporting all of the black people to Africa or Central America or excluding them from the new territories.

Lincoln Opposed the Extension of Slavery into the New Territories Because It Artificially Inflated the Congressional Power of the Democratic Party

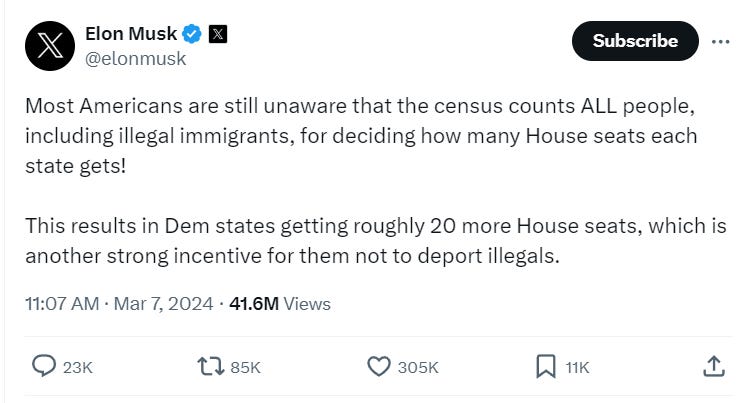

On March 7, 2024, Elon Musk posted on X (formerly Twitter) a complaint about how the modern day Democratic Party unfairly receives extra Congressional representation based on how things are counted by the census.

Interestingly, Lincoln and the Republican Party also complained about the Democratic Party because, back then, the Democrats were receiving an artificially inflated number of Congressional seats. This sounds like a common complaint coming from Republicans. Lincoln complained about the three-fifths clause of the Constitution because it “allowed every five slaves to account for three persons for purposes of determining the number of congressional seats in each state, which has always been a function of a state’s population.”19 The three-fifths clause, according to Lincoln’s complaint about it, gave “each white male South Carolinian two votes in Congress for every one vote for a man from Maine, because of the former state’s 384,984 slaves.”20 DiLorenzo concedes that this was legitimate Republican opposition to slavery but then adds that it was “not on moral grounds.”21 Once again, DiLorenzo impeaches (i.e., challenges or questions) Lincoln’s moral character.

The North's Horrific Treatment of Blacks

The final section of this chapter is an extended discussion about how Northerners treated blacks. DiLorenzo provides a very long list of horrible things done to blacks in the North. The list is so long that I feel it is necessary to truncate it or this article will never end:

Negroes were systematically separated from whites, excluded from railway cars, omnibuses, stagecoaches, and steamboats or assigned to special “Jim Crow” sections22

Blacks were educated in segregated schools, punished in segregated prisons, nursed in segregated hospitals, buried in segregated cemeteries23

Black Codes existed in the North. As an example, the Revised Code of Indiana

prohibited Negroes and mulattos from coming into the state

made all contracts with Negroes null and void

punished whites, such as employers, who encouraged blacks to enter the state

prohibited Negroes and mulattos from voting

banned interracial marriage

forbade Negroes and mulattos from testifying in court against whites

forbade them from sending their children to public school

forbade them from holding public office24

Blacks were prohibited from residing within the new territories or required to post a bond of up to $1,000 that could be forfeited for “bad behavior”25

Blacks were allowed to vote in a few Northern states (Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine) but were often victims of voter intimidation.26

Northern labor unions did not accept black members and vigorously opposed abolition. They lobbied for laws and regulations that would prohibit blacks from competing for jobs held by whites.27

Blacks were victims of mob violence, especially mob violence from Irish immigrants who saw free blacks as direct competitors for their jobs.28

Why does DiLorenzo dwell on this topic of the North’s horrible treatment of blacks for so long and with so many gory details? DiLorenzo gives two reasons. His first reason is that

the foregoing discussion calls into question the standard account that Northerners elected Lincoln in a fit of moral outrage spawned by their deep-seated concern for the welfare of black slaves in the deep South. Blacks in the North were treated horribly and were institutionally deprived of the most fundamental human freedoms by the myriad Black Codes and by discrimination and violence.29

In other words, DiLorenzo is undermining the credibility of the Lincoln scholars and their “official story” about the War between the States. I think he is also trying to say that Northerners have no moral high ground. DiLorenzo is just being consistent. Earlier in this chapter, he spent a lot of time impeaching the moral character of Abraham Lincoln (calling him a liar, for example). Now, in the latter part of the chapter, DiLorenzo attacks the moral character of Northerners. He seems to want to say that Northerners and their primary representative, Abraham Lincoln, were moral monsters. Sometimes I think he wants to go even further by arguing that the North was morally inferior to the South. For example, DiLorenzo cites Tocqueville who wrote that “the prejudice of race appears to be stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists.”30

His second argument addresses the issue of Northern enlistment in the Union army that invaded and conquered the South. Here is what DiLorenzo writes on the topic of Northern enlistment:

It is conceivable that many white supremacists in the North (which included most of the population) nevertheless abhorred the institution of slavery. However, given the attitudes of most Northerners toward blacks, it is doubtful that their abhorrence of slavery was sufficient motivation for hundreds of thousands of them to give their lives on bloody battlefields, as they did, during the war. It is one thing to proclaim one’s disdain for slavery; it is quite another to die for it.31

DiLorenzo does not tell us why Northerners enlisted in the Union army. He simply says that they did not die for the blacks. Their intense hatred of blacks strongly suggests that they fought in the war for other reasons. Perhaps Northerners fought and died for the benefit of whites (since they were white supremacists). Perhaps they thought that fighting the war was in the best economic interest of whites (the only way for white free labor to finally beat black slave labor). DiLorenzo’s reply to this train of thought is rather brilliant. If Northerners had adopted the peaceful emancipation idea used by many other countries they would have peacefully saved white free labor. DiLorenzo explores the issue of peaceful compensated emancipation in much more detail in the next chapter of his book.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 304, 10-11.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 10.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 13.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 13.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 12.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 11.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 11.

Murray N. Rothbard, “America’s Two Just Wars: 1775 and 1861,” in The Costs of War: America’s Pyrrhic Victories, ed. John V. Denson (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1997), 131.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 16.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 18.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 16-19.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 18.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 21.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 21.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 21-22.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 295.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 12-13.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 22.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 23.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 24.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 24.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 25.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 25.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 25-26.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 27.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 28.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 29.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 30.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 32.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 25.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2003), 32.